Processed food can repeat India’s automobile export success

Despite Covid, agricultural exports boomed in 2020-21. Export earnings can go up if India shifts focus from primary processed agricultural commodities to value added processed food products.

In the economic nightmare caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, rising exports of agricultural commodities has provided a cheerful diversion. The estimates reported by the Ministry of Food Processing Industries show the average value of export of processed food to be $32.8 billion from 2015-16 to 2019-20. The share of agricultural and processed food products in India’s total exports has been 11 per cent during this period with a much higher share of primary agricultural commodities. The export earnings can go up if India can export value added processed food products rather than the primary processed agricultural commodities.

In this article, we discuss the average export of 48 key agricultural and processed food products (tracked by the (Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority, or APEDA) from 2015-16 to 2019-20 and compare it with the exports in 2020-21.

Despite the Covid-19 pandemic, agricultural exports boomed during 2020-21. The earnings (of APEDA products) have significantly increased from a five-year average of $17.8 billion (from 2015-16 to 2019-20) to $20.65 billion in 2020-21. Most of these items are from agriculture and allied sectors with minimal processing.

Changing export scene of non-basmati rice, poultry meat

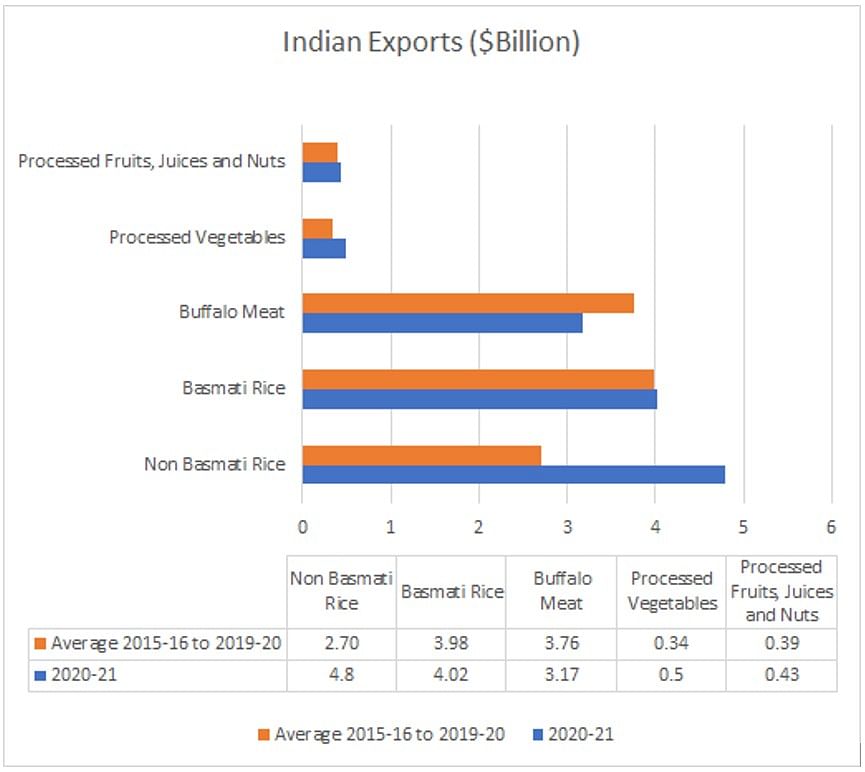

There has been an unusual spike in the export of non-basmati rice, which earned more foreign exchange than basmati rice. In 2020-21, India exported 13.09 million tonnes of non-basmati rice ($4.8 billion), up from an average 6.9 million tonnes ($2.7 billion) in the previous five years.

The export of basmati rice in 2020-21 (4.63 million tonnes at $4.02 billion) followed the trend of 2015-2020 five-year average (4.19 million tonnes with earnings valued at $3.98 billion).

This increase in the export of non-basmati rice took place despite a huge increase in the procurement (at minimum support price, in the form of paddy) by the government in 2019-20. We also see that rice procurement increased from five-year average of 41.2 million tonnes to 58.6 million tonnes in 2020-21 (difference between kharif marketing season and financial year is not accounted for). The average unit price realisation per tonne of non-basmati rice was $366.5 in 2020-21 compared to $391.6 in the previous five years. Indian rice is still quoting $40-$50 lower than the comparable Thai rice (25 per cent broken grains).

The Ministry of Commerce and Industry will do well to look deeper to find out the sources of export of non-basmati rice. It is feared that the leakage of rice from the public distribution system may be contributing to lower prices (quoted by rice exporters), and hence leading to higher exports. There is also a huge environmental cost in the terms of over use of groundwater and its quality. Agricultural economists Ashok Gulati and Ritika Juneja and others have been writing about the implied export of water when rice and sugar are exported from India. At the same time, the Indian government has been encouraging their exports to meet an ambitious target of $60 billion of exports by 2022 and thereafter to $100 billion under the Agriculture Export Policy, 2018. This will not be an easy task if a lower value, non-basmati rice exports decline over the next ten years, as they should, in order to save the underground water.

The downward trend of export of buffalo meat (cara beef) continued and export earnings in 2020-21 went down to $3.17 billion from an average of $3.7 billion during the 2015-2020 period. It had touched $4.78 billion in 2014-15. Lower exports were due to restrictions imposed by China on import from Vietnam and Hong Kong, which were the major importers of buffalo meat from India. Indonesia offers a great potential but only the government agencies are allowed to import buffalo meat and there is a quota for its import from India. India, on the other hand, allows free import of palm oil from Indonesia through private sector. Trade negotiators need to push for greater market access to Indonesia.

In 2020-21, the exports of poultry, sheep and goat meat have also gone down. The export of guar gum also dropped from the 2015-2020 five-year average of $0.55 billion to $0.26 billion in 2020-21.

Meeting the challenges, fixing the gap

A major objective of the Agriculture Export Policy 2018 has been to diversify the export basket so that instead of primary products, the export of higher value items, including perishables and processed food, be increased. It is also envisaged that the growing global market of organic and novel agricultural products will be tapped into.

However, the export of processed food products has not been growing fast enough because India lacks comparative advantage in many items. This may imply that the domestic prices of processed food products have been much higher as compared to the world reference prices. Besides, the exporters of processed food confront difficulties and non-tariff measures imposed by other countries on Indian exports. Some of these include:

- Mandatory pre-shipment examination by Export Inspection Agency is lengthy and costly

- Compulsory spice board certification is needed even in the ready to eat products which contain spices in small quantities

- Lack of strategic plan of exports by most of the state governments

- Lack of predictable and consistent agricultural policy discouraging investments by the private sector

- Prohibition of import of meat and dairy based products in most of the developed countries

- Withdrawal of Generalised System of Preference (GSP) by the US for import of processed food from India

- Export shipments to the US require an additional health certificate

- Absence of equivalency agreement with developed countries for organic produce

It should be appreciated that the export of processed food of higher value can be undertaken best by companies having reputed brands that can meet the global standards of Codex. In fact, some countries have fixed even higher standards for import of food items. Indian companies have to be cost competitive and adopt the latest technology to enter into the global markets in a big way.

The central government should enable and nurture companies to keep the cost of production low and meet the global food quality standards. The production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme proposes assistance for the manufacture and export of four major food product segments – ready to cook/eat foods, processed fruits and vegetables, marine products, and mozzarella cheese.

While PLI is an attractive scheme for Indian corporates, a more supportive environment is needed to make export of processed food as successful as the auto exports from India.

As a regulator, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India has its task cut out.